The concept of truth can be broken down into at least two categories; objective truth and moral truth. Objectively true statements are true for all of us regardless of how any of us feel about them, e.g. “Most rocks are hard”, “The Sun is a star”, “Water is two parts Hydrogen and one part Oxygen”. These statements cannot be reasonably disagreed with when they are appropriately translated. There may be a communication hurdle when attempting to describe objectively true claims but, once all relevant descriptions of the phenomena are performed effectively, there should be collective agreement among all reasonable parties. Objective truth is the category that we are most often referring to when we evoke the concept of truth at all. In this realm, factual claims can be known to be true or false. The realm of objective truth is the realm of knowledge. It is commonly understood that objective truth refers to a reality that exists independent of observation. If you and I are on a hillside looking at an olive tree, it should be agreed upon by us both that when we leave that hillside the tree will continue to exist as it seemed to exist while we were observing it even after neither we nor any other person are looking at it. Still, the olive tree only entered our objective reality, the realm in which objective claims are made, after it was observed by us both. When that agreement is in place, we have an objective reality.

Knowledge and belief can be understood as differentiated levels of confidence in an objective claim. Objective claims can be falsifiable or unfalsifiable. Falsifiable claims accepted with a very high confidence level are said to be known or knowable. Falsifiable claims accepted at any confidence level can be believed or disbelieved. Unfalsifiable claims can only be believed or disbelieved. This is how I separate the realms of knowledge and belief. We can know what we see, hear, taste, touch, or smell. We can also know what we detect through telescopes, microscopes, radar, sonar, and a host of sophisticated mechanical detectors. I can know that you told me you put 5 apples in the basket because I heard you say those words but I can’t know there are actually 5 apples in the basket unless I see them for myself. Scientific experimentation, scientific investigation, and scientific thinking generally has brought us a richness of objective knowledge about our shared reality that our ancestors couldn’t have imagined. We celebrate this accomplishment, as we should, but it has hard limits that are worth recognizing.

Objective reality is constituted by a collection of first-hand subjective testimonies. Healthy objective reality is constituted by a collection of true first-hand subjective testimonies. Subjective experience comes first. The only extant phenomena you can’t doubt is your own subjective experience. By yourself, there’s no objective reality. If you are truly alone, there’s no one to be objective with and objectivity never comes into play. You might notice patterns in your subjective experience that lend themselves to being understood as existing independently of your subjectivity but, if you are truly alone, the objective reality you perceive will remain untestable and unfalsifiable. The test for our objective shared reality is the concordance of at least two subjective testimonies. This idea echoes Matthew 18:20 minus the name of Jesus. If you accept that I’m offering a subjective testimony that is independent of yours and I accept the same in kind, we together have constituted an objective reality.

Let’s say I’m awake and alone and have always been alone, as far as I know. I see things come and go but none of those things seem to notice me in any meaningful way. They whiz and whir seemingly according to their own purposes. I am the only part of this environment that isn’t being directly controlled by it. Suddenly, you appear. You seem to possess an autonomous subjective freedom in much the same way I do and we begin to communicate.

You: “Is that a brick?”

Me: “I call that a bram.”

Y: “What’s behind this wall?”

M: “That’s not a wall. That’s a window.”

Y: “We should move towards that dark area over there.”

M: “I see that dark area. We should not.”

The first disagreement will remedy itself quickly once we decide on a common term for the rectangular prism that’s flipping around like a clock gear, a “brickam” or a “bramick”. The hard part of this first type of disagreement about objective truth is that we can be saying the same thing in different words and, if neither of us are inclined to re-evaluate our own definitions, we can get stuck on a simple disagreement indefinitely. The second disagreement is stickier. We can agree that we have a generally flat plastic surface that acts as an impassable physical barrier but what do I see in it that you don’t? Let’s say, I see a landscape beyond this plane that betrays our position as being in a very low building in the middle of a vast field of grass. You see solid slightly textured dark gray plastic. As long as there are only our two testimonies, we remain at an impasse. I know what I see. You know what you see. We have a quantum superposition of objective claims on what can be known about our collective situation. If a third person arrives and substantiates your claim, immediately I become wrong and ignorant about the truth with respect to the appearance of this wall. Objective truth and knowledge would, in the wall situation, be on the side of you and our friend. You guys could claim to “know” that the plastic was not transparent and was in fact opaque with a very high level of confidence. Does this mean that I should cease “knowing” that the plastic is transparent? No. I should understand the popular knowledge as best I can and continue to testify truthfully about my first-hand experience. If I see grass, I should say that I see grass. It’s important that each of us testify truthfully about our experience. Maybe I’m hallucinating. Maybe the plastic has microscopic slits in it such that the grassy field outside can only be seen through the plane from exactly where I’m standing and, if you or our friend, stood exactly there, you would see through the window much as I do. Refusing to attempt to see a situation from the perspective of one you disagree with is a surefire way to inhibit your own cognitive development. I should try to see the plastic how you see it before deciding that I’m right and you’re wrong. I’ve found that everyone I meet is doing what they feel is right all the time. There’s a tautology there but it’s better than wilting in a cognitive box of my own construction. What will eventually be objectively true for all of us might originate as only subjectively true for some of us. The Freedom of Speech as ascribed in political constitutions is potently meaningful for this reason amongst others.

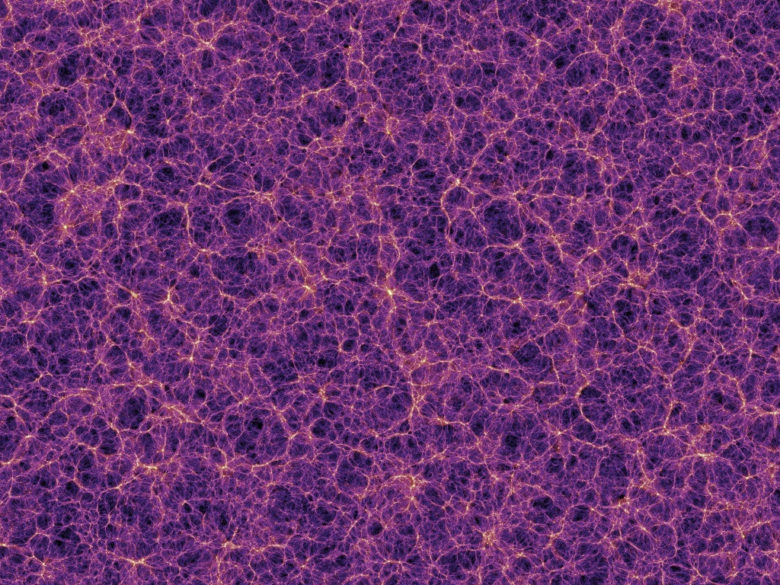

It stands to reason that there are probably innumerate phenomena that currently “exist” within the physical bounds of the observable universe but those phenomena are not part of our objective reality yet because they’ve not been detected widely enough to be agreed upon. Facts are affirmations of falsifiable claims that are widely agreed upon by reasonable people. If, in the previously illustrated example, 999 people looked at the plastic from your perspective and only yours, it would be a fact in that society that the plastic wall was gray and opaque. If those people moved from your spot to mine and back again, it would be a fact that we had a plastic plane that appeared opaque from one viewing angle and appeared transparent from another. A fact, as I’m arguing it here, is not a transcendently extant feature of physical reality as it actually is. A fact is a phenomena detected, observed, or measured by direct physical sensation or technological extension of physical sensation by the majority of reasonable people. 99.9% of society can be wrong about a widely held “fact”. The Earth was flat for a very long time. The underlying actual real truths of base reality that our “facts” point to remain mysterious but our facts seem to be getting better and better over time. Scientific observation is exactly the practice of examining our shared reality from as many viewing angles as possible so we don’t collectively linger as flat Earthers for any longer than we have to. We can know or fail to know facts about our shared reality. We can choose to conscientiously object to popularly known facts. Sometimes we should. I propose that the best ideas will win in time and I don’t think there’s any need to silence the unpopular ones. If truth means anything, it means that which cannot be soiled or destroyed. You can temporarily hide the truth. You can bury it for yourself and from others but, I suspect, what is true will outlast us all regardless of how we behave in its presence. The prudent and fruitful path is to consciously elevate the concept of objective truth and to honor the phenomena that we can collectively agree upon when you see windows and I see walls. Objective truth, as a concept, is popularly understood and relatively straightforward. Moral truth is trickier.

The last disagreement in our thought experiment is a moral one. Most discussions about what we should or shouldn’t do take into consideration the facts of a present-tense mutually agreed upon objective reality and they assume the specific details of a future objective reality are somewhat an outcome of the choices we make right now. The mechanism of the human will is complex. I’m aware of the merits of the argument for physical/mental determinism. I fully subscribe to the logic of my brain-state being indistinguishably embedded in the state of the universe at any given moment in time and the state of the next moment depending fully on the composition of the previous. One deterministic idea is that the future is as set in stone as the past when considered from an objectively removed standpoint. When I think about quantum and molecular physics as a lay, no other conclusion seems reasonable. Still, the concepts of choice and responsibility are meaningful for personal moral improvement. In this reality, we’re currently prohibited from doing experiments in time. The notion that I could have done differently if I knew differently is unfalsifiable because I can’t go back and redo that moment, no one can. The notion that what will happen was always going to happen is equally untestable. Those ideas strike me as rhetorically reasonable but there’s no way to know if either of them are demonstrably true without performing time travel. Therefore, those claims fall outside of our objective reality and outside the realm of what can be known. We can’t know if things could have gone differently than they did. We can, however, know what we did and how things went as a consequence. Those conceptions are subtly and meaningfully different. We can’t know if things can go differently than they will because we have no way of detecting any moment in time other than this one. But we can use knowledge about the observed patterns of behavioral consequences to make intelligent predictions about possible shared futures. You can believe physical/mental determinism is the way our minds work but you can’t know it.

Morality is the utilization of observed patterns of positive and negative consequences of behavior to assist us in making mutually beneficial and healthy progression towards a collective goal. We can know that a given behavior led to a given outcome is a past scenario because we detected those behaviors and those outcomes. We can reasonably gather that similar behavior will produce similar outcomes in future situations like that aforementioned one but we cannot know that that is the case because the past will not literally repeat itself. It’s highly likely that future situations, even with striking resemblance to the past, will have meaningfully different variables. Let’s take the Golden Rule (GR) in a popular form, “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.” People who commit suicide by cop can shoot guns at officers’ chests until the cops fire back and, in that moment, be acting out this rule verbatim. The GR is not explicitly life affirming. We assume that you yourself want to live a nice life and the GR therefore encourages you to help other people live nice lives. Maybe you want to thrive impressively, maybe you want to eat without making waves, either way we move towards our collective goal. I’ve surmised that our collective goal is to multiply as far as we can. RNA, DNA, and organic cells themselves have laid that groundwork. We seem to celebrate life affirmation and condemn life negation. Those ideas make sense to me. I believe in them but I can’t know them. I’ve detected that we wanted to live in my past. I detect that we want to live now. But, I have not detected that we will want to live. I think we will. I hope we will. But I cannot know that we will. That’s an improper use of the concept of knowledge as I define it. We can know which collective and individual behaviors worked for mutual benefit and which didn’t. We can know, loosely, what behaviors are working now and which aren’t. But we cannot know exactly how such behaviors will take us towards the panacea or towards the cliff. We can make reasoned arguments and intelligent predictions using the knowledge that we’ve acquired thus far as the basis for moral reasoning. Still, moral reasoning almost always lands us in the realm of belief. Which is a perfectly healthy place to land but it should not be conflated with the realm of knowledge.

You are expecting your father to knock on your door at 1pm on a Saturday. It’s 12:59 pm and you hear a knock. It’s reasonable to say that you believe your father is at the door. It’s unreasonable to say that you know your father is at the door. In the narrow sense, we could here take know all the way down to “The only thing you know is that you exist” but that would lose sight of a popular and meaningful understanding of the concept of knowledge. For the above example, there could be a neighbor, a delivery person, or a malicious robotic dog at the door. All you know is the time, your expectation, and the sound you heard. A belief cannot itself have a truth value. Most beliefs, when phrased appropriately, possess an underlying factual claim that does have a truth value. The truth value of “I believe my father is at the door.” depends entirely on the truth value of “My father is at the door.” The veracity of the belief depends completely on the veracity of the factual claim(s) underneath it. Knowledge is limited to what we can detect and have detected directly through our senses or through their technological extension. We can’t know what is best for humanity in the long run because we’ve never done the long run before. This is our first time existing as a species. As far as we know, none of us have experience leading a nascent civilization into a multiplanetary or multisolar culture. Whenever we invoke an idea about what humanity “should” do, we’re guessing. That’s not to say we don’t make very educated and well reasoned guesses. I’m a huge fan of Jordan Peterson’s work. I’m a proponent of his moral admonitions. That said, I think I draw a difference with him on the way he prescribes building a moral knowledge base.

He claims that we can use our innate sense of meaning along with scientific reasoning about psychological and societal facts to investigate, discover, and know moral truths. He once said that if a person holds a proposition in mind and that proposition leads them to objective success in some arena then that serves as evidence that that proposition is true. Let’s take the proposition, “You should be nice to people.” and consider the following factual claims, “You are nice to people.”, “Your friend gave you an unsolicited gift because you’re nice to him.”, “Your boss gave you that promotion because he watched how you treat your teammates and was very pleased with your behavior.” I think Jordan would argue that the initial moral claim is an inescapably logical result when these factual claims are shown to be true. I would agree that initial moral claim is logical, reasonable, useful, helpful, prudent, and wise but I would not go so far as to say that we can know it’s true. Generally, one can’t know how one should behave. One can only believe or disbelieve in moral claims.

There is at least one scenario in which one can know what should and shouldn’t be done. There’s a mechanic working on a car engine and he says “There should be an A-type connector between these two components”. How can he make that claim? Because he knows how a finished engine of that type should be assembled from bottom to top. He has knowledge of the entire engine’s state when it’s complete and uncompromised. We don’t have that same top to bottom knowledge about this reality or our future society. We’re not blind but when you imagine what base reality must be compared to this one and the amount of interactions we are capable of having with it, we’re one eyed at best. We can often use the word “should” with knowledge level confidence when discussing the things that we’ve made. We can only use that word with belief level confidence when discussing the things that made us.