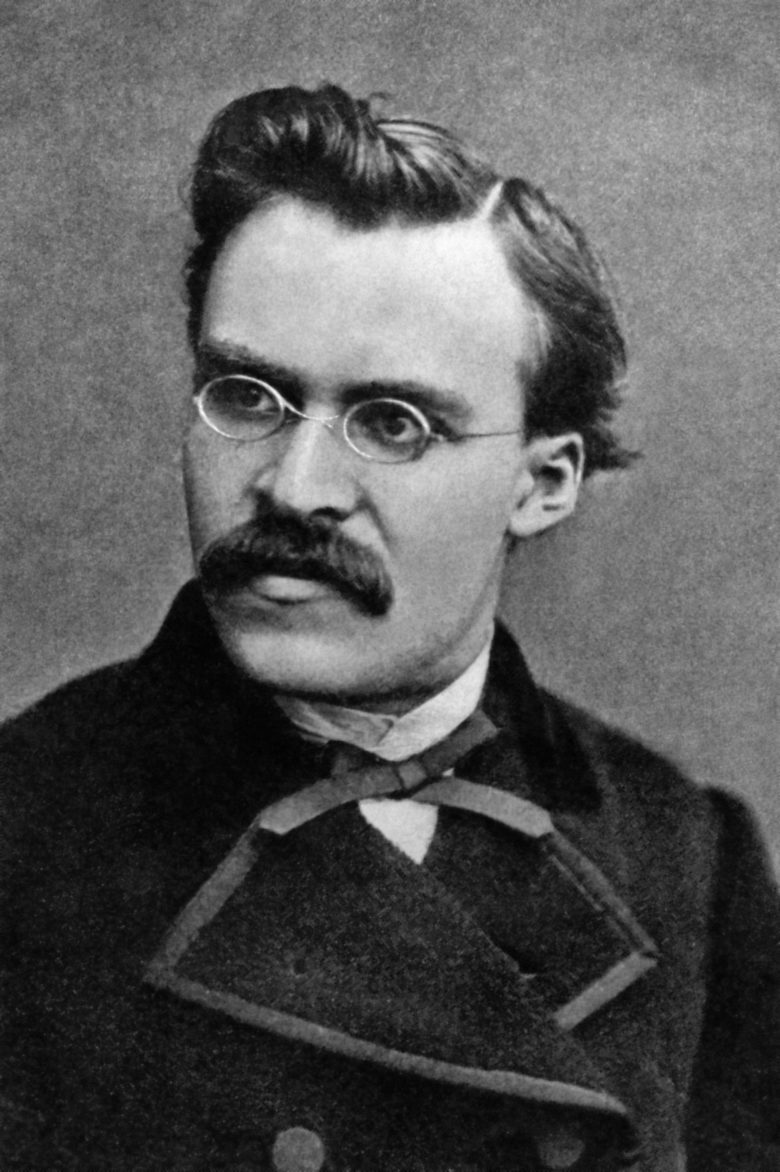

Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a book written by Friedrich Nietzsche between 1883 and 1885. I’m not remotely qualified to write a “review” of the book that could be taken as serious literary critique, so I won’t. This article is a layman processing his thoughts, feelings, and reactions after reading the work for the first time. I’m grateful that Friedrich lived and wrote as he did. I’m grateful that Jordan Peterson speaks so highly of him. This isn’t an exhaustive representation of the themes contained in the book. Nor is it a collection of every passage that impacted me profoundly. If this article piques your interest in Professor Neitzsche’s work, I suggest picking some of it up and reading it. Chances are, it’ll change you.

Zarathustra is a character created by Nietzsche whose real life namesake is Zoroaster the founder of Zoroastrianism. The fictional Zarathustra is not exactly a man and not exactly a god. He occupies a middle space much like Jesus of Nazareth. I’m confident that there are a great many Christian and Zoroastrian allusions in this text that passed over my head without event. The narrative structure of the book is mostly us, as readers, following Zarathustra around as he hikes up, down, around, and over mountains. We listen to him as he has discussions with spirits, animals, and humanish figures in towns, islands, and hillsides. The narration frequently gives us insight into Zarathustra’s or another characters’ thoughts but the lion’s share of the text is Zarathustra speaking in the first person, hence the book’s title. In this article, I’ve quoted some of Zarathustra’s philosophy in the order in which I encountered it and I briefly touch the concepts of the Higher Man and Pity at the end. Leave a comment below if you liked the article. Thanks.

~~~

“Oh, my friends, that your self be in your deed as the mother is in her child — let that be your word concerning virtue!” – On The Virtuous

What resonates with me most in this passage are the many ways in which a mother is in her child. Genetically, the child is half her, the child’s microbiome is almost entirely hers, if not entirely, and she remains in the child, in these ways, for the duration of the child’s life. If a person can accept that every action they take, from picking up a pencil to picking up a felony, will live independently in the world from that point on with their DNA and their maternal signature embedded permanently in its core and can accept responsibility for the consequences of that action, positive and negative, then they are one step closer to being the most forthright and upstanding citizen they can be.

“On the tree, Future, we build our nest; and in our solitude eagles shall bring us nourishment in their beaks. Verily, no nourishment which the unclean might share: they would think they were devouring fire and they would burn their mouths. Verily, we keep no homes for the unclean: our pleasure would be an ice cave to their bodies and their spirits.” – On The Rabble

I read this passage as inspiration for the visionary and the leaders of tomorrow. If you are one of those visionaries, I think this encourages you to have faith that the ideas that ring so true to you but sound so crazy to less courageous people will bear fruit. There’s a secondary benefit that comes with being willing to walk out onto intellectual limbs. It’s that none of the intellectually timid will follow you there. You’ll be like Andrew Yang in the 2020 presidential race. The other candidates wish they had the courage to back the Freedom Dividend but they haven’t put in the thought necessary to act as warm coats defending the principles behind the dividend when the cold hatred of the naysayers arrives.

“Yet his thirst does not persuade him to become like these, dwelling in comfort; for where there are oases there are also idols.” – On the Famous Wise Men

Zarathustra is wandering through a desert here, in search of transcendent truth I think, and he is very hot and very tired. He sees that he could take refuge in some nearby shade as others were already but he dared not. As we wake, suffering from one day to the next, it is very tempting to take refuge in the common ideology of our fellows. “Get a good job and be happy.”, “God has it all under control”, “Don’t worry.”, “Keep working hard and it’ll work out.”, “Love thy neighbor”, “Never, ever give up”, these phrases represent some of the philosophical shade we rest under. Zarathustra never fully accepts even the most profound ideas he encounters. He applied them and, when they worked in practice, he abided in them but he never fully accepted them as transendantly true and neither should we. I abide by “Keep working hard and it’ll work out.”, “Love thy neighbor”, and “Never, ever give up”. Those ideas are very powerful in practice but I don’t accept them as transendantly true. The transcendent truth is unknown. It’s a point of focus that recedes at the speed of our approach. Zarathustra’s spirit settled for nothing less than that pursuit. Neither should ours. To be sure, that journey is very painful, hence the thirsty in the desert metaphor, but I think it’s worth it if you can get on board.

“And this is the second point: he who cannot obey himself is commanded. That is the nature of the living.” – On Self-Overcoming

I read this as saying he who cannot develop self-discipline will become and remain disciplined by others. I’m confident there are many other ways to read it but that’s the interpretation that resonated with me.

“And life itself confided this secret to me: ‘Behold,’ it said, ‘I am that which must always overcome itself.’ Indeed, you call it a will to procreate or a drive to an end, to something higher, farther, more manifold: but all this is one, and one secret.” – On Self-Overcoming

The sentiment contained in this passage ties to the Cognitive-Theoretic Model of the Universe, at least the fraction of the CTMU I’ve tried to internalize. The idea of a thing that must always overcome itself screams self-configuration to me. How is it that I could begin to overcome myself? I would have to have a drive that is both within me and outside of me. That force would have to be inside me such that it could generate real movement in my mind and decision making. That thing that is outside of me is the small fraction of the physical universe that has interacted with at least one of my five senses. We are made of stardust and there’s no triviality in that. The human genetic code contains secrets that we have yet to unlock and it is the thing to which we owe our nature and our ability to imagine. What did Nietzsche know of the relationship between double stranded DNA, the Periodic Table, and Quantum Electro Dynamics? We don’t exist as personalities at the level of the quantum but, whatever quantum dynamics actually are, they are the reality that undergird and construct the undergirding of what we experience as beings made of molecules made of atoms. Let’s say that Nietzsche had an inkling as to what base algorithms all human brains run. He spent a lot of time paying attention to the emulsions of his own tortured psyche. I think he gained tremendous insight into all of our shared human nature with this effort and much notable insight into the operation of nature herself.

“That I must be struggle and a becoming and an end and an opposition to ends – alas, whoever guesses what is my will should also guess on what crooked paths it must proceed.” – On Self-Overcoming

Assuming the moral perspective of Zarahthustra, each of us has to try to be the conductor of our own train, walk to the beat of our own drum, carry the world on our shoulders, and stand as strongly and as straight we can. The entirety of reality is coming to bear on you in this very moment in no exaggerative terms. What should you do with that information? You should thrive. How do you thrive? In part, you predict threats from as far away in time and space as possible. What constitutes a threat? One potential threat is a strong man standing, struggling against the weight of the world and succeeding, who is also within his attacking distance of you. Guessing what he might do, helpful or harmful, before he does it might be the difference between the gutter and the mountaintop for you in the near term future. You should do that.

“Of all evil I deem you capable: therefore I want the good from you.” – On Those Who Are Sublime

This is a theme that I hear Jordan Peterson emphasizing quite a bit. How good is a person who can only do good? Not very good at all. It is my current belief that Jesus of Nazareth was tempted the way we are all tempted, i.e. he got considerations in his mind and feelings in his chest to break his fast and later to commit suicide. Considering the framework I’m carrying forward now, Jesus might have been VERY tempted, in the way we use the word for ourselves, and entirely capable of breaking his fast, committing suicide, and/or kneeling before the devil. The big idea here is that it was his capacity to do evil and his subsequent refusal that made him a good human being. I’m not a Christian. I think Mary got pregnant the old fashioned way. Nonetheless, it seems to me that Jesus of Nazareth was a remarkable human being worthy of being listened to and understood as completely as we can. The idea for us is that you should be capable of evil acts but you shouldn’t perform them. Put another way, if you can’t be a threat to anyone, you can’t be good for anyone. If you want to be a protector of life, a protector of your family, or a protector of your ideals, you have to have the capacity to be a threat in some meaningful dimension. Some of our protectors are the best among us when their choice to behave well is a deep choice that could have gone another way.

“Where is innocence? Where there is a will to procreate. And he who wants to create beyond himself has the purest will.

Where is beauty? Where I must will with all my will; where I want to love and perish that an image may not remain a mere image. Loving and perishing; that has rhymed for eternities. The will to love, that is to be willing also to die. Thus I speak to you cowards!” – On Immaculate Perception

The passage that contains this quote begins with a metaphor in which the moon, with its cold aloof crawling midnight stare represents dishonesty and a lack of innocence. I think Nietzsche is deriding those people among us who, because they feel they can’t joyfully participate in any act of creation in common and/or popular ways, they instead declare themselves completely objective, refuse to get their hands dirty by participating in commoner’s activities, and/or convince themselves that they are so unlike the regular lay person that they have acquired an ability to operate as a pure observer. Nietzsche announces that they are not innocent in their perverse analysis. He is also criticizing himself through this lens as Friedrich Nietzsche spent most of his time pale, sickly, alone, and skilly deconstructing people’s glaring and subtle personality flaws. Epic doesn’t begin to describe the scope of his idea contained here. The “innocence” here is not lack of guilt. It is action despite the presence of guilt. If you create art, people, or both there’s an innocence in that. “Where I must will with all my will” is the birthplace for all that would be willed. It is the place where any effort less than full effort is faulty failure. It is where the rubber meets the road and the lazy dare not step. It is the place that will burn and/or freeze everything but pure love. How are we to conjure, discover the pure love that wants to live in our own hearts? That is a difficult and worthy task for us all. Is it worth dying for? I’m tempted to argue that that’s all that’s worth dying for. To love so intensely that it erases all of who you thought you were before you’ve had a chance to resist. To be compelled to imagine with your full bright intelligence and to act with your special reserved cunning on behalf of someone else, anyone else, especially someone that you love. That is where the spirit of Zarathustra would have us go.

“For ‘punishment’ is what revenge calls itself; with a hypocritical lie it creates a good conscience for itself.” – On Redemption

It seems to me that rage, outrage, revenge, and punishment have a conceptual overlap. There’s an element of enthusiasm inside of what enrages us and what we declare as outrageous. Those ideas contain a positive tinted enthusiasm that shows up with a unit of pleasure attached in its sidecar. Often, too often, we want to be outraged because it feels good. This is self-righteous hedonism. Revenge can be understood as harm returned to another for harm done to us, an eye for an eye. The harm returned component of revenge is where it overlaps with rage. To want to return harm is to want revenge. To be able to do harm is to rage. Revenge or rage can be first on the scene and the presence of one increases the likelihood of the arrival of the other, subjectively pleasureable in either order. Punishment can be understood as harm returned for harm done in order to prevent further harm. When a person fantasizes about applying a punishment without considering deeply whether or not that punishment will prevent further harm, they are only seeking revenge. One should not be pleased to mete out punishments. When a punishment must be given, it means that something has gone wrong. It means that someone has misbehaved. It means that we have collectively failed to properly demonstrate the beauty of “First, do no harm.” and “Your freedom ends at the tip of my nose.” to one of our own. We are also at fault when we must give a punishment and we punish in the spirit of improving the punished. Revenge has no such spirit. It doesn’t look inward for fault or look outward for strengthening its target. “Punishment” applied in such a way is the desire to torture masquerading as benevolence. That’s why it’s hypocritical.

“And so let me shout it into all the winds: You are becoming smaller and smaller, you small people! You are crumbling, you comfortable ones. You will yet perish of your many small virtues, of your many small abstentions, of your many small resignations. Too considerate, too yielding is your soil. But that a tree may become great, it must strike hard roots around hard rocks.” – On Virtue that Makes Small

Zarathustra is walking, as a giant, through a town who, along with it inhabitants, is ever shrinking. I think they are shrinking because their impact on the future is becoming less and less and life evolves. The inhabitants have a custom of being ultra kind, ultra polite, ultra yielding, never bold, never outstanding, never rude. It’s beautiful that each of us is a tree and each of us is soil. As a tree, we want to have people around us that are bold, outstanding, and sometimes rude. The tougher they are the tougher we can grow to be. As soil, we should be stubborn, unyielding, and difficult to pass such that anyone who does challenge themselves to challenge us will be made that much better by the effort.

“The lust to rule: the earthquake that breaks and breaks open everything worm-eaten and hollow; the rumbling, grumbling punisher that breaks open whited sepulchers; the lightning-like question mark beside pre-mature answers.” – On The Three Evils

What does it mean when someone rules as a result of lusting to rule? It likely means that they aren’t the best person for society. I interpret this quote as saying often those that lust to rule are only equipped with old ideas. If these unworthy leaders burrow their way into positions of power then they bring with them dead ideas that would better remain dead. They create unnecessary crises to appear relevant. They confuse the masses, muddy the waters, and waste energy in the service of their immature lust. I think that’s part of what makes their lust evil.

“To will liberates, for to will is to create: thus I teach. And you shall learn solely in order to create.

And you shall first learn from me how to learn – how to learn well.” – On Old and New Tablets

In hindsight, this is one of the most timeless quotes in the book. I’m grateful that it stood out to me as I read it. I’m grateful to Professor Nietzsche for writing it. There’s no interpretation necessary. It’s just beautiful.

“But you who are world-weary, you who are earth-lazy, you should be lashed with switches: with lashes one should make your legs sprightly again. For when you are not invalids and decrepit wretches of whom the earth is weary, you are shrewd sloths or sweet-toothed, sneaky pleasure-cats. And if you do not want to run again with pleasure, then you should pass away.” – On Old and New Tablets

Stop feeling sorry for yourself. It seems to me that when one is feeling sorry for oneself they are acting out as world-weary and earth-lazy. We all get world-weary at times and, at those times, we should be lashed. Therefore, it was very keen to write “if you do not want” in this quote because it is those that have given up on running again that most deserve this word lashing.

“Let him lie till he awakes by himself, till he renounces by himself all wariness and whatever weariness taught through him. Only, my brothers, drive the dogs away from him, the lazy creepers, and all the ravenous vermin – all the raving vermin of the ‘educated,’ who feast on every hero’s sweat.” – On Old and New Tablets

I think Nietzsche is speaking here about those occasions in which the upright get world-weary and it serves as a warning about allowing oneself to remain weary for too long. Those parasites and leeches that imagine their strength as attacking the flaws of the strong will run to devour you like a horde of ants to a wounded dragonfly.

“This, however, is the truth: the good must be pharisees – they have no choice. The good must crucify him who invents his own virtue. That is the truth!” – On Old and New Tablets

This goes back to the idea of the good being those in society that are unable to do bad things. Those good people are the keepers of the average. Subconsciously, they make great efforts to prevent anyone that appears to be getting out of line from getting out of line without giving any critical thought as to what differentiates one type of stepping out of line from another. They are rule followers and good employees. They are not the best employees and they can’t be leaders. It’s likely that they know he who invents his own virtue has the capacity for evil and they calculate that it’s better to prevent the truly virtuous from doing anything new than allowing him to grow stronger than their opposition. The emaciating helplessness one feels upon encountering one who is much stronger and has the capacity to wipe you out, if they turn against you, is furiously warred against in the mind of the good.

The Higher Man and Pity

In the fourth part of the book, Zarathustra has a collection of characters gathered in his cave: the king at the right and the king at the left, the magician, the pope, the voluntary beggar, the shadow, the conscientious in spirit, the soothsayer, and the ugliest man who had adorned himself with two crimson belts. I think these characters represent what we commonly consider the best characteristics of men in our society described as the worst; their worst traits and our worst understandings of their roles. One should read into the passages that describe Zarathustra’s interactions with these characters very deeply. I’ve tried my best to understand and internalize the lessons these passages contain. My understanding is not complete. For brevity, the descriptions that follow will not even represent my entire understanding of the passages about higher men and pity. I heartily recommend reading the source material for yourself and gaining your own understanding. You won’t regret it.

Pity is one of the central concepts in the text. We learn at the end of the book that Zarathustra’s greatest sin is having pity on the higher men. Why would having pity on these men be a great sin?

Having pity on the king at the right and the king at the left is a great sin because his pity allows them to continue to lie to themselves. I think the king and the right and the king at the left represent intelligent, powerful people respectively reigning from the liberal and conservative points of view. Each of them succeeds in understanding the basic flaws in their own perspectives and privileged positions. The only reason they cross paths with Zarathustra is because they too seek higher truth. When he has pity on them and he allows them into his cave, he becomes another person who was taken in and fooled by their apparent righteousness.

Having pity on the magician is a great sin because the magician cannot tell the truth and Zarathustra believed him for a moment to have pity on him. Zarathustra saw that the magician pretended to be an ascetic with a mix of acting and seriousness. He called the magician out on exactly that charge. Then, when the magician admitted that he himself was not great. Zarathustra believed that admission and took pity on him. That was the sin! The magician is stupid and a perennial mix of truth and lie. He should never be believed or believed in.

Having pity on the pope is a great sin because the pope claims to know what he cannot know and he never renounces that claim. I define knowledge as those phenomena that can be detected directly by our physical senses or indirectly by mechanical extensions of our senses; microscopes, telescopes, and sensors. It seems that Nietzshe may have considered that definition of knowledge as well. Even at his most doubtful, the pope maintained “in what pertains to God, I am – and have the right to be – more enlightened than Zarathustra himself.” Any person that claims enlightenment with regard to phenomena that cannot be detected is undeserving of pity and it’s a sin of he who would pity to offer it to them.

Having pity on the voluntary beggar is a sin because Zarathustra, with good intentions, led the voluntary beggar away from peacefulness and into the company of the ass (donkey) worshiping higher men. The voluntary beggar was once a rich person who forsake his riches to live amongst the common people. The common people rejected him and he found himself in the company of a herd of peaceful cud chewing cows. He was in a field successfully sermonizing to and learning from the cud chewing cows when Zarathustra interrupted his peace. The voluntary beggar’s nature is one to ask questions and honestly listen to the answers that are given. The voluntary beggar is a carefully trusting man. Zarathustra should have seen that the voluntary beggar was in a peaceful position, doing his own thing, and doing it well. Zarathustra should have known at that moment to leave well enough alone. Sometimes it’s best to let sleeping dogs lie. Zarathustra sinned when he failed to realize that this was one of those times.

For Zarathustra, having pity on the shadow is a sin because the shadow is his own. The wickedness is his own. The lust, hubris, and eager evil are his own. Should he have pity on himself? Of course not. Zarathustra commits a sin when he has pity on this unrepentant troublemaker and when he fails to realize that the shadow is his self.

Having pity on the conscientious in spirit is a sin because it is a waste of pity and a waste of energy. The conscientious in spirit is a proud, confident, knowledgeable, and humble man. Zarathustra accused the conscientious of being wrong about who realm the conscientious was in. The conscientious said he was in his own realm hunting leeches and Zarathustra said he was in fact inside of Zarathustra’s realm performing the hunt. Zarathustra didn’t understand the realm to which the conscientious was referring. He was not referring to the physical realm in which his body happened to be. He was referring to the mental realm in which he has lived and will finish his life. He is the conscientious in spirit and an expert on the brain, of leeches above all. The conscientious did go to the cave and worship the ass but he probably would have done that without any pity from Zarathustra. The lesson for us all; don’t have pity on the proud. It’s a waste of energy on your part and will have no effect on those at whom you aim.

Having pity on the soothsayer is a sin because the soothsayer instigated Zarathustra’s pity in the first place. He tempted pity out of Zarathustra to support his own self righteousness. The soothsayer deceives himself when he believes he prophecies for others, even when his prophecies are accurate, because he is the self fulfilling soothsayer who doesn’t take responsibility for his role in the events that he predicts.

Having pity on the ugliest man is a sin because he is the hypocrite that lives in our hearts. The ugliest man is the one who killed God. The ugliest man kills and laughs about killing. He’s the unremorseful psychopath pretending to enjoy himself. However ugly we think he will be, when we meet him, he’s uglier. He destroys when he’s sad and he destroys when he’s happy. He’s not death because death is a sweet release. He’s a torturer and a reviver and he’ll never admit it. Having pity on him is an obvious sin. The real question is; Why is the ugliest man included among the higher men? These are the personalities that are meant to lead us from the abyss. He’s included because there’s no most beautiful without the ugliest. Our angels and our demons are teammates.